It’s hard enough, in a white supremacist patriarchal culture, to admit you need help or can’t do it (all). That you’re human, meaning: that there’s nothing wrong with you, you just can’t.

So when I saw the headline “Naomi Osaka withdraws from French Open, citing her mental health,” my heart hurt for her, and also buoyed up a bit, at what I read as the strength to make this (not doubt) difficult call.

In my own way, I related to having to say no after saying yes to work, in times when I simply couldn’t because: my grandmother died, my partner needed help after surgery, my mother-in-law died… all of course, we understand reasons to say “I can’t”… and yet, in each case, even as I knew what I needed to do, I experienced a flurry of guilt about not following through. About letting other people down when I had made a promise.

It’s indicative of my internalization of white supremacist patriarchal cultural norms and requirements (Okun):

- How “I’m the only one” (they’re counting on me!)

- How it’s either/or (either succeed or fail, be reliable or flaky)

- How the work is urgent (we can’t reschedule!)

- How my life (and all the people involved in it) should operate with clockwork efficiency, so that work is never inconvenienced

… that I don’t actually endorse or want to inflict on myself or others.

So, yeah, I was sorry and glad for Naomi when I read that she won’t play in this tournament.

And then I was sad and furious when I read:

Following her decision to opt out of media duties last week, the French Open was criticized for posting a tweet — which it has since deleted — with photos of Rafael Nadal, Kei Nishikori, Aryna Sabalenka and Coco Gauff engaging in media duties with the caption: “They understood the assignment.”

Not furious about the criticism. Furious about the cultural mindset behind the tweet.

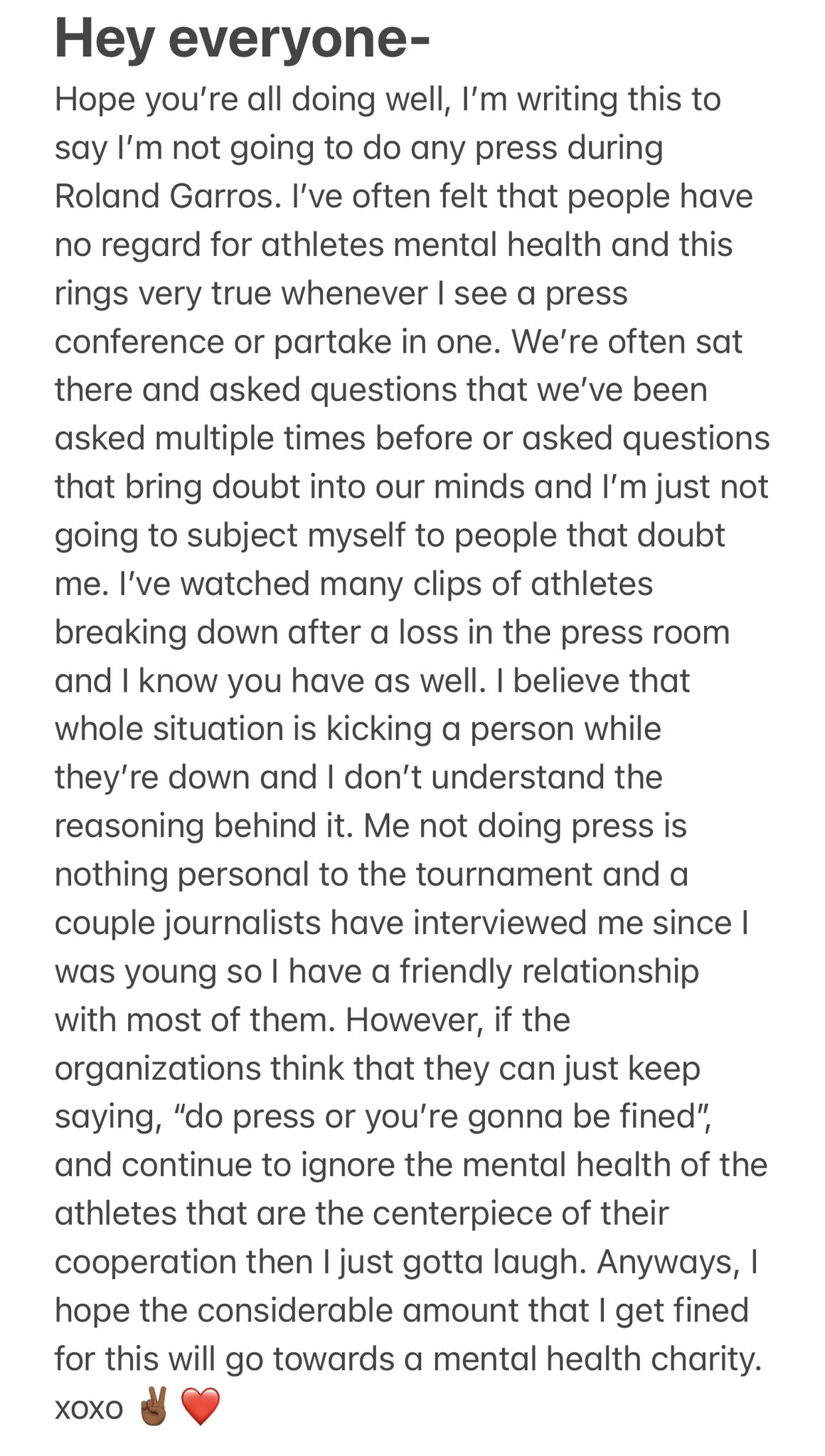

I get that the tone of Naomi’s announcement about not doing press was a call-out:

Apparently the federation felt like Naomi was reneging on their agreement, although in acknowledging that she would pay the fine as the consequence of her decision, Naomi actually indicates her intention to honor the agreement.

Regardless of Naomi’s decision or perceived “tone” (because oh, there’s so much here about a Black woman not just not obeying, but also calling out the establishment), there’s no excuse for the federation’s public, snarky dismissal of a member of their own community’s statement of the need for more humane workplace culture and expectations.

It’s a shame that the French Open tried to shame Naomi. It’s a shame that they couldn’t see the opportunity here. Because this is how equity and inclusion – to realize the safety, dignity, belonging and thriving of all, not just some, in our communities – advances: through questioning some of the most fundamental assumptions about “how things work.” Through wondering why “this is how we do,” when it costs us our humanity. Through sifting through what we do to identify the why, and then considering how else we might achieve our aspirations (e.g. people getting to know the players and understanding what it’s like to compete at such an elite level, players getting to process their experiences and share with their fans) that is more humane, inclusive and restorative of self and community.